An Early Holiday Treat for Stargazers

As the year advances into the month of December, sunrise times occur much later in the morning, while sunset times occur much earlier. Here in southern New England the latest sunrise is around 7:13:09 a.m. on January 2, whereas the earliest sunset is around 4:14:58 p.m. on December 11. Despite the usually increasingly cold nights, amateur astronomers are able to begin their observing sessions soon after the dinner hour. Therefore, December is welcomed by many stargazers since it offers many hours of dark skies…as long as a bright Moon does not intervene.

During mid-to-late November, for those of you who commuted to work in an easterly direction had surely noticed a brilliant beacon above the east-southeast horizon before sunrise. That dazzling object was the planet Venus. Venus will continue to dominate the morning sky as December begins. A beautiful sky scene will greet your eyes on the morning of the 3rd as a waning crescent Moon will appear about six degrees above our planetary neighbor.

Joining Venus during early December will be our solar system’s closest planet to the Sun—Mercury. On the 5th the waning crescent Moon will pass about six degrees above and to the right of Mercury. Mercury will continue to ascend into the sky until the 10th after which it will then begin to descend back towards the horizon and the Sun. Around this time, depending upon your view of the horizon, you may begin to see the return of Jupiter. Each morning Jupiter will rise higher into the sky as Mercury is setting. On the 22nd these two worlds will appear within one degree (two full Moon diameters) of each other. So if you’ve never observed Mercury try using Jupiter as your guide to do so. By month’s end Mercury will disappear from view in bright morning twilight.

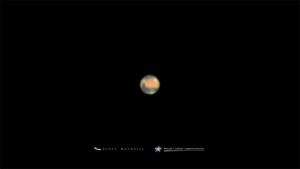

While Mars continues to be visible throughout December, the distance between our two worlds increases from 94,469,737 miles to 117,172,414 miles by month’s end. That means the image size of the planet through a telescope will continue to shrink. I suspect Mars’ surface detail will be difficult to discern in smaller instruments. Consider how much the Earth has pulled out ahead of Mars in our respective orbits. Back at closest approach at the end of July the Earth and Mars were a mere 35,785,537 million miles apart.

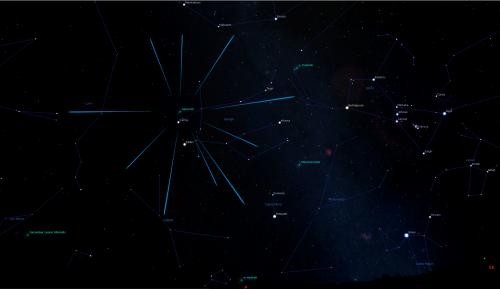

I always look forward to the northern hemispheres’ best shooting star display —the Geminids. With the peak of meteor activity on the night of December 13-14, I regard this showers’ appearance as an early holiday gift from the Universe. And for 2018 if weather conditions are favorable about 60+ meteors per hour may be seen from about 10 p.m. once the waxing crescent Moon sets until the sky begins to brighten during dawn. With no interfering moonlight stargazers will have an opportunity to see as many meteors as possible. All you will need is a dark-sky location devoid of interfering light pollution sources.

An observer can usually count on the temperature to be at or below the freezing mark during the Geminids. Regardless, I still recommend sitting or reclining in a comfortable lounge chair. Dress in layers. Climb into a sleeping bag if possible. Wear a hat to keep heat from escaping through your exposed head. Wear warm mittens, not gloves. Mittens keep your fingers together for added warmth. You can also use a few of those pocket warmers to keep extremities toasty.

Keep warm and alert, but don’t get too comfy out there. I’ve told the following story many times since it occurred, but it is a cautionary tale that bears repeating.

Many moons ago during a Geminid meteor shower watch from Seagrave Observatory, the sky was clear when we started observing. However, sometime during the night we all fell asleep. When we awoke we realized some clouds had paid us a visit, since we were all covered with a dusting of snow. Moral of that story is…stay awake while meteor observing during the winter. Otherwise they may have to pick you up with ice tongs and thaw you out in the morning!!

One important fact to remember if you cannot observe the Geminids throughout the night until dawn is that this shower is one that can be observed before midnight. You won’t see the peak rate of meteors, but you will see more than you could on any random night of sky watching. And there can be one advantage if you observe within a few hours of sunset. You may catch a few Geminid earth grazers as they skim tangentially across the top of Earth’s atmosphere and parallel to the horizon. This scenario provides for much longer streaks, often looking like a stone skipping across a pond.

While the Geminids appear to radiate from Gemini near its brightest stars, Castor and Pollux, scan around the sky as much as possible. As the night progresses and Gemini moves across the sky towards the west, your scan should move as well. At around 2:30 a.m. Gemini will be on your north/south meridian, just south of zenith. The number of meteors per hour should increase throughout your observing session. You’ll know you’ve seen a Geminid if you can trace the origin of the meteor’s trail back to the radiant point.

The Geminids are fairly bright and moderate in speed, hitting our atmosphere at 21.75 miles per second. They are characterized by their multicolored display (65% being white, 26% yellow, and the remaining 9% blue, red and green). Geminids also have a reputation for producing exploding meteors called fireballs. The source of the particles that comprise this meteor stream is a two-mile-in-diameter hybrid “rock comet” named 3200 Phaethon. The Earth sweeps through its orbital path annually.

And finally, it doesn’t seem possible that winter is nearly upon us in the northern hemisphere. On the 21st the Winter Solstice occurs at 5:23 p.m. EST (Eastern Standard Time). Notice how low an arc the Sun now travels across the sky. After this date and time the Sun’s arc will rise higher and higher each day as it appears to travel northward in our sky, reaching the Vernal Equinox (spring) on March 20, 2019 at 5:58 p.m. EDT (Eastern Daylight Time). The apparent shift of the Sun’s position in the sky is the result of the Earth’s fixed axial tilt of 23.5 degrees as our planet orbits the Sun. Watch the following video for a review of this process:

Seagrave Memorial Observatory in North Scituate is open to the public every clear Saturday night. Ladd Observatory in Providence is open every clear Tuesday night. The Margaret M. Jacoby Observatory at the CCRI Knight Campus in Warwick is open every clear Thursday night. Frosty Drew Observatory in Charlestown is open every clear Friday night year-round. Be sure to check all the websites for the public night schedules and opening times before visiting these facilities. These observing sessions are free and open to the public.

David A. Huestis

- Author:

- David Huestis

- Entry Date:

- Dec 10, 2018

- Published Under:

- David Huestis's Columns