Celebration of Space - January 14, 2022

The Full Wolf Moon of 2019, just before the start of a total lunar eclipse. Credit: Frosty Drew Astronomy Team member, Scott MacNeill

On Monday, January 17, 2022 at 6:51 pm EST, the January full Moon will occur, bringing with it copious amounts of moonlight that will light up the potentially snow-covered Southern New England landscape. The January full Moon is also known as the Full Wolf Moon. Which was likely named due to the increased awareness of wolves howling during this time of the year. At Frosty Drew, we do not have any wolves, but we do have a good deal of coyotes, which generally become much more chatty during the colder months of the year. The January full Moon will also happen when the Moon is closer to its apogee (furthest point in its orbit). The lunar apogee for the current 23.7 day cycle occurred this morning, January 14, 2022 at 9:29 am, which placed the Moon at a maximum distance of 252,155 miles from Earth. Step outside just after sunset on Monday, and look to the NE horizon to catch the Full Wolf Moon rising.

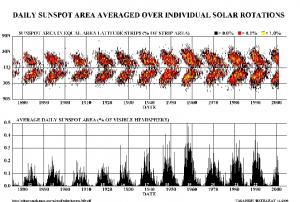

Over the past several months, activity on the Sun’s Photosphere, the atmosphere of the Sun that we generally think of as the surface of the Sun, has seen a significant increase in sunspot activity. This is not all together abnormal considering the Sun is moving towards solar maximum. What is unexpected is the level of activity which we are seeing, which is more intense then the predicted level of activity.

The Sun has an eleven year sunspot cycle with a high point in activity (solar maximum) and a low point (solar minimum). During solar maximum, sunspot activity is very high and the photosphere is usually littered with sunspots at all times. Alternatively, during solar minimum the photosphere is devoid of sunspots, sometimes for over a month’s time. With the increased sunspot activity of solar maximum will also come increased solar flare activity and coronal mass ejections (CME). Which, among other things, are a result of sunspot instability.

Sunspots form due to the rising of solar material (granules) carrying energy from the radiation zone of the Sun, through the convection zone, and arriving at the photosphere. At which point the granules will release their energy and sink back down. Granules are magnetized with a N and S polarity and will connect with other granules that are also releasing their energy. If enough of these granules connect, they will remain on the photosphere and form a small magnetic field over them. This magnetic field will shield the granules from surrounding solar radiation, allowing the granules to cool, resulting in a darker region of the photosphere, a sunspot. The magnetic field is not stable and will eventually break open, releasing a magnetic push on the chromosphere and corona, which sit over the photosphere. This push will allow a higher concentration of plasma in the solar corona to enter the solar wind. This is a CME. Since plasma is electrically charged, it has magnetism and when a CME arrives at Earth, the charged particles will bombard Earth’s magnetic field, peeling it back. Charged particles will attach to Earth’s magnetic field lines and travel into the atmosphere over the polar regions of Earth. Once these charged particles encounter the denser ionosphere, they start to strike oxygen and nitrogen atoms, ionizing them. This is what causes the Aurora Borealis, aka the Northern Lights.

Solar Cycle 25 began in December 2019, during solar minimum. Cycle 24, which peaked in April 2014, was a rather weak solar maximum, and it was predicted that Cycle 25 would be similarly weak. Looking at past sunspot count graphs, the trend shows that solar maximum moves in quite quickly, which then slowly tapers off to solar minimum. As Cycle 25 ramps up, we are seeing more sunspot activity than what was predicted, which could mean a more active solar maximum than we had in 2014.

During solar maximum, I often hear doomsayers go on about how a huge solar flare is going to wipe out life on Earth, which is complete nonsense. To the contrary, solar maximum is safer for inhabitants of Earth compared to solar minimum. The solar wind, which is a constant stream of plasma and energy that is released from the Sun, has a small amount of amperage. This is called the Heliospheric Current Sheet. During solar maximum that amperage will fluctuate, which will allow for increased deflection of cosmic rays. Additionally, during solar maximum, Earth’s magnetic field is bombarded with increased activity in the solar wind, which causes it to balloon out, which will also deflect more cosmic rays and solar radiation. During solar minimum, the amperage in the Current Sheet normalizes. Additionally, Earth’s magnetic field gets a bit lazy from the lack of solar activity and shrinks. Both will allow a higher level of cosmic rays and solar radiation into Earth’s atmosphere.

So get ready for potentially higher sunspot activity than expected during Cycle 25, which could check off the Northern Lights on your bucket list of awesome.

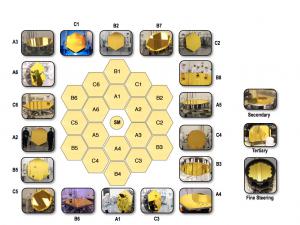

This past week, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has moved into a state of Fully Deployed. The next step, which is already underway, is to align and fine tune the individual mirror segments to function as one huge mirror. Additionally, the secondary mirror, which sits at the tip of the telescope, has been released from its launch stabilizing mechanisms. The process of performing the alignment of each mirror segment will take a period of three months. After which, the observatory will function as one large telescope. Though still in transit to Lagrange Point 2 (L2), which is just under 1 million miles past the Moon, JWST will arrive at L2 during the mirror segment alignment procedure. Arrival at L2 and integration into a halo orbit at that location will be the next big milestone. For the telescope geeks out there, here is a great resource to learn a bit about how the James Webb mirror segments work. Sit back on this cold night with a cup of toasty deliciousness, a fluffy kitty or pooch, and catch up on the operations of this fantastic observatory.

- Author:

- Scott MacNeill

- Entry Date:

- Jan 14, 2022

- Published Under:

- Scott MacNeill's Columns